I believe that dungeons should always be heavily xandered.

…

Okay, it’s true. I’m just making up words now. Recently, though, I’ve been doing some deep dives into the earliest days of D&D. I’ve been reading and running the rules and adventures of those bygone days and discovering — or rediscovering — the amazing work of Arneson, Gygax, and the many, many others who were exploring the brave new world of roleplaying games. When it comes to xandering the dungeon, what I wanted was a word that capture the pioneering dungeon design of Blackmoor, Greyhawk, and, above all, Jennell Jaquays, who designed Caverns of Thracia, Dark Tower, Griffin Mountain, and a half dozen other old school classics for Judges Guild, Chaosium, Flying Buffalo, and TSR. Because a word for that didn’t exist yet, I felt compelled to create one.

This article originally coined a different term. Click here for an explanation.

I first started running Jaquays’ Caverns of Thracia last year. It inspired an entire campaign, and while exploring its depths with my players over the past several months I’ve often found myself ruminating on the mysteries of its labyrinths and trying to unravel why it’s such an utterly compelling and unforgettable adventure. Along the way, I’ve come to the conclusion that everyone should be more familiar with Jaquays’ amazing work, so let’s take a moment to dive deeper into her legendary career and also consider what makes a dungeon adventure like Caverns of Thracia different from many modern dungeon adventures.

After amazing work in tabletop RPGs, Jaquays transitioned into video game design, and in that latter capacity she recently wrote some essays on maps she designed for Halo Wars:

Memorable game maps spring from a melding of design intent and fortunate accidents.

Jennell Jaquays – Crevice Design Notes

That’s timeless advice, and a design ethos which extends beyond the RTS levels she helped design for Halo Wars and reaches back to her earliest work at Judges Guild.

And what Jaquays particularly excelled at in those early Judges Guild modules was non-linear dungeon design.

For example, in Caverns of Thracia Jaquays includes three separate entrances to the first level of the dungeon. And from Level 1 of the dungeon you will find two conventional paths and no less than eight unconventional or secret paths leading down to the lower levels. (And Level 2 is where things start getting really interesting.)

The result is a fantastically complex and dynamic environment: You can literally run dozens of groups through this module and every one of them will have a fresh and unique experience.

But there’s more value here than just recycling an old module: That same dynamic flexibility which allows multiple groups to have unique experiences also allows each individual group to chart their own course. In other words, it’s not just random chance that’s resulting in different groups having different experiences: Each group is actively making the dungeon their own. They can retreat, circle around, rush ahead, go back over old ground, poke around, sneak through, interrogate the locals for secret routes… The possibilities are endless because the environment isn’t forcing them along a pre-designed path. And throughout it all, the players are experiencing the thrill of truly exploring the dungeon complex.

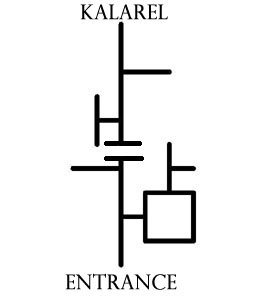

By way of comparison, Keep on the Shadowfell, the introductory adventure for D&D 4th Edition, is an extremely linear dungeon:

(This diagram uses a method laid out by Melan in this post at ENWorld. You can also find a detailed explanation in How to Use a Melan Diagram.)

Some would argue that this sort of linear design is “easier to run”. But I don’t think that’s actually true to any appreciable degree. In practice, the complexity of a xandered dungeon emerges from the same simple structures that make up a linear dungeon: The room the PCs are currently in has one or more exits. What are they going to do in this room? Which exit are they going to take?

In a linear dungeon, the pseudo-choices the PCs make will lead them along a pre-designed, railroad-like route. In a xandered dungeon, on the other hand, the choices the PCs make will have a meaningful impact on how the adventure plays out, but the actual running of the adventure isn’t more complex as a result.

On the other hand, the railroad-like quality of the linear dungeon is not its only flaw. It eliminates true exploration (for the same reason that Lewis and Clark were explorers; whereas when I head down I-94 I am merely a driver). It can significantly inhibit the players’ ability to make meaningful strategic choices. It is, frankly speaking, less interesting and less fun.

So I’m going to use the Keep on the Shadowfell to show you how easy it is to xander your dungeons by making just a few simple, easy tweaks.

XANDERING THE DUNGEON

Part 2: Xandering Techniques

Part 3: The Philosophy of Xandering

Part 4: Xandering the Keep on the Shadowfell

Part 5: Xandering for Fun and Profit

Addendum: Dungeon Level Connections

Addendum: Xandering on the Small Scale

Addendum: How to Use a Melan Diagram

Dark Tower: Level Connections

[…] take the shortest path between two points!) Of course, in dungeon layouts that are insufficiently [xandered]; and in games where the playing time for combats take 10 times as long as those in B/X […]

[…] of the book, this particular dungeon isn't the greatest dungeon or map in the world. I plan on [xandering] the dungeon (and changing some of the encounters, which is beyond the scope of this post). At the same time, I […]

[…] [Xandering] the Dungeon, a multi-part article series from The Alexandrian about how to create non linear dungeons in the fashion of Jennell Jaquays‘ Caverns of Thracia and Dark Tower, two classics published by Judges Guild in the late 70s. The components of good dungeon design discussed in this article can indeed be ported to modern dungeons. […]

[…] Я уже писал ранее о нескольких игровых сессиях, которые я провёл в его заброшенных залах. Я также использовал его в качестве примера того, как можно сделать ваше собственное подземелье «в стиле Жако». […]

[…] Я уже писал ранее о нескольких игровых сессиях, которые я провёл в его заброшенных залах. Я также использовал его в качестве примера того, как можно сделать ваше собственное подземелье «в стиле Жако». […]

[…] Карта должна быть большой, а также вдумчиво проработанной «в стиле Жако». […]

[…] detail in the documents below, I was a bit unsatisfied with this location. I was also intrigued by Justin Alexander’s article on “[Xandering] the Dungeon”, a method of using design ideas from the dungeons designed by Jennell Jaquays to make dungeons more […]

[…] С оригиналом Вы можете ознакомиться здесь […]

[…] and options to get around certain areas without being unable to progress at all. The Alexandian wrote about this a while back and I very much recommend reading his thoughts on the […]

This series (plus observations of real-world places) has given me basically my entire approach to map design.

I’m still getting the hang of how to do it properly — for instance, my last adventure put all the monsters in dead-end rooms, so the players had little reason to move through loops — but it’s been a key factor in every adventure I’ve run so far.

[…] you’ve yet to read the wonderful series of essays at The Alexandrian called [Xandering] the Dungeon, you should line that up. Its findings aren’t mindblowing, but the clarity of dungeon […]

I never bothered to actually read the EN World post you shared until now, and man, shame on me : it’s a great read, and a great tool to make dungeons better.

The subsequent posters also exemplifies pretty well the “Railroad is fun” motto. 🙂

Cross-posting an interesting video series on The Legend of Zelda dungeon design, which has some interesting parallels with your blog series.

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLc38fcMFcV_ul4D6OChdWhsNsYY3NA5B2

[…] therefore introduced the concept of “ghoul tunnels” to [xander] the map and connect different areas. I placed these at the bottom of pit traps or in rooms that already […]

[…] with you. The first and foremost inspiration was Justin Alexander’s article “[Xandering] the Dungeon“. It is one of many, many articles on The Alexandrian that I will be referencing during this […]

As the images on the ENWorld forum thread have since been lost to the web, I went hunting for any other details and found the following, a copy of Melan’s original post with images still intact:

http://www.darkshire.net/jhkim/rpg/dnd/dungeonmaps.html

[…] The Alexandrian has a decent series of articles relating to this issue which you can find here. […]

[…] en text som ofta hänvisas till beskriver The Alexandrian vad han anser vara god design för en megadungeon i allmänhet och vad […]

[…] out, but I had them all drawn fairly close to each other, so I cannot say that the dungeon was well [Xandered]. [Jennell] Jacquays does a lot in her designs to avoid railroading and creating quantum ogres, and my […]

That’s make perfect sense in the Dark Souls video game’s, especially the first one. The feeling of exploration is huge, due to the interconnections and the choices they bring.

Great stuff! Can I translate it to spanish?

E-mail me at the address in the About link (in the right hand column at the top of the page) for translation queries.

[…] told by the writer to the reader, with only a passing thought given to actual play. This utterly non-[xandered] funhouse dungeon is a level of silliness we should have left behind with TSR’s Slaver […]

[…] The choice of a mega-dungeon for the school has been resolved: I aim to run the acclaimed “Caverns of Thracia” module, which has been the subject of so many excellent reviews and actual play reports as to catch my attention. Combining this with B/X Essentials will be a pretty cool combo, methinks. In truth, however, reading it and pondering upon the contents has convinced me to [xander] my dungeons. […]

[…] players along a linear path, the dungeon teases explorers with perils and routes to discover. In a study of designer Jennell Jaquays’ dungeon maps, Justin Alexander explains how a well-connected dungeon gives groups agency and flexibility. […]

[…] Lair” published in The Dungeoneer 11 in 1979 did not embody the design principles outlined in [Xandering] the Dungeon even though it was created by the person whose name would become synonymous with the […]

[…] Also, the number at the bottom ([Xandering] Number?? | for more see this post, which references this series of posts) , gives a measure of non-linearity of the adventure. A completely linear adventure e.g. Room 1 […]

[…] are spelled out in a five-part series of posts on The Alexandrian titled [Xandering] the Dungeon here, here, here, here and […]

[…] make the dungeon appear more linear looking to the players. To increase interconnectivity, hence ‘[xandering]-the-dungeon’, simply add a few more pegs (e.g. 3) at […]

[…] are spelled out in a five-part series of posts on The Alexandrian titled [Xandering] the Dungeon here, here, here, here and […]

[…] not the first to write about this. In fact, I aim only to summarize some high-level takeaways from the Alexandrian blog post on this. I believe that site coined the term, but I don’t know for sure. In any case, what follows is […]

[…] Temple, one map for the ground floor, one for the catacombs. Then I redrew the maps after reading an (awesome!) article about “[Xandering] the Dungeon”, which gave me some insights I felt I needed to incorperate in my adventure. I will probably redraw […]

[…] The “Jaquays” style dungeon has multiple loops, connecting different areas of the dungeon, rather than being (essentially) in a straight line. This style also includes multiple connections between levels, both consecutive (between levels II and III) and otherwise disconnected (between, say, levels III and V). There is an excellent article at the Alexandrian about this style of non-linear dungeon design. […]

[…] проектирования подземелий не универсальны в CRPG. В этой замечательной статье The Alexandrian говорится о «дизайне подземелий jaquay», в […]

A quick comment to thank you for this awesome article!

There are a lot of articles and videos about how to improve your game/dungeon/NPC (you name it), but this one is really a gem.

The Hexcrawl article is also very nice.

Nice article. I’m running an immense dungeon at the moment called “The Halls of Arden Vul” written for OSRIC, but I’m using 5e because we’re on roll20 and it has good support, and also because it’s what my Players wanted.

What’s great about Arden Vul is that it truly could be played twenty times over and have completely different results. There are entry points and exit points and chutes that drop you five levels deeper with no regard for what level the PCs are. There are creatures not remotely made to be taken on by low level groups, and there are factions that are doing their own thing. Interacting with them or even killing them will often have a completely unintended effect which I as the DM have to take into account.

It’s a blast and for all the 5e modules I have bought nothing comes close to it. The hardcovers from WoTC feel a lot like you’re reading the script for a play.

[…] are nonlinear, make good use of 3D and verticality, have enough connections and looping to fit the [Xandering] the Dungeon […]

[…] Cavern. The first blogpost to truly get hooked on the idea of the OSR was the Alexandrian’s [Xandering] The Dungeon. It was here that my mind started opening to the idea of building worlds, not stories. Finally, […]

[…] to use based off of the point network. And, ideally, each layer of the network would be suitably [xandered], and the connections between layers would [xander] the whole […]

I’ve been reading this series of articles and it’s dawned on me that there is some basic information not mentioned that I don’t know.

How do you actually present the dungeon to your PCs? Do you run it theater-of-mind? Do you draw the room the players are in only if combat erupts? Many of these techniques assume the players can’t see the whole map, or have no idea of the geography during non-combat time. You assume players have to map their way through the dungeon to know where they are.

I’ve only been DMing for 2 years, and my entire experience has used online VTTs. I draw my dungeon maps in map-drawing programs, and then manipulate the “fog of war” with dynamic lighting to restrict my players’ view. Lot’s of the techniques mentioned in this series just don’t work with this method (for example, slight inclines in paths, or other ways to obfuscate geography). It’s a lot harder to confuse the players when the map exists, in one hand-drawn piece uploaded to the VTT.

This also leads to other tactical issue. My party has 3 players, but many NPCs accompanying them. Most of these dungeons have 5-foot wide hallways. This means I have this very long conga-line of players moving their tokens about. If the player at the front enters a room and starts combat, people at the back may need to spend their whole turn just walking to the encounter, and that’s no fun.

There’s also the question of how to run non-combat movement in these digital battlemaps. Should I allow them to move their tokens around by their free will? Or should I instead run the dungeon as a sort of “node structure” where I let the players choose “I take the left door” and then teleport them to the next room or intersection down that hallway? What about random encounters during dungeon travel? I shudder at the thought of running a whole combat encounter in a long 5-foot wide hallway.

I’d love to be able to use more of these classic dungeon-planning techniques, but they just seem so incompatible with the digital battlemap style.

The closest I’ve personally come to using a VTT is a shared Google Slides document, pasting pieces of map one room at a time. I would imagine the way to make a sloping corridor work in a VTT is to find an excuse to swap the map when they players aren’t looking, or to just swap it and when they ask “huh, what happened?” give your best DM shrug and say “What do you mean, what happened? Nothing happened.”

Five-foot hallways are wider than the hallways in a lot of houses. People can pass each other, but probably take a half-step out of each other’s way. You’re welcome to decide for yourself what amount of PCs trying to pile past each other in a hallway fight — nothing says you have to stick to the letter of whatever’s in the rules, if it’s making things not be fun.

That said, you’re not the one who should be afraid of a hallway fight. Your *players* should be afraid of a hallway fight. Give them something scary blocking the hall where only one or two of them can properly engage and the rest have their line-of-sight obstructed by their friends. Even better, have the scary thing sneak up on them from behind and melee with the squishy casters while the fighter has to struggle back through the lines to be able to even help.

If you’ve never done dungeon-delving without all the video-game trappings of VTTs and dynamic lighting and fog-of-war, try sometime doing without it. You might like it, or anyway, you might learn some stuff that you can keep doing even with VTTs. You’re not running a video game, and you don’t have to limit yourself to only doing stuff that fits in a video game.

But backing off from the details, at a higher level, most of [xandering] is about making maps with loops and branches with meaningful choices in them, and none of *that* is any different no matter how you present it, full VTT or scrawled maps on a dry-erase board or pure “you enter a 20×20 room with doors on the north and east walls”. Your players still get to have the option of saying, “you know, maybe we should try going the other way first.”

“You’re welcome to decide for yourself what amount of PCs *can* pile past each other in a hallway fight”

I think I’d enjoy running the game without a VTT, but I use it more as a necessity than a convenience. My players are my high school friends, who are all now in different cities or states for college. It’s a lot easier to run once a week online than organize flights to the same place to have an in-person game. I only had a few months of in-game play experience in high school, so I never got the chance to learn much via “osmosis”. My old DM, now one of my players, wasn’t all that experienced either. That’s why I find this entire blog very useful, as a sort of replacement for what I might have learned naturally over decades of play and after reading hundreds of adventures.

My only real in-person dungeon-delving experience was with my wizard-barbarian bugbear (my first character ever) in a kobold lair. I took command of the kobolds by proving my might, and then promptly got disintegrated by the lightning breath of a mechanical dragon the kobolds accidentally dug up, and that we accidentally activated. A very interesting and memorable experience haha. I recall we used a dry-erase marker on a reusable grid to draw out the cave system and move between the areas.

Switching out the map during play is a good idea. It’s pretty easy to do if I have the other map as an invisible layer that I toggle on/off on top of the current map. I’ve actually done that in previous sessions for evolving environments (players were fighting evil kuo-toa while two kuo-toa archpriests battled each other, summoning tsunamis that flooded the map for a few rounds every time). I haven’t had the opportunity to use that often though because I am running Out of the Abyss, and it has painfully little in terms of dungeon-crawling (or anything else for that matter). It requires a lot of work to maintain.

I really like making pretty maps, but I can see how it puts some limits on play. For one, it’s time-consuming to make a new map for practically every combat encounter. It also sets unintentional rails on where a combat encounter starts. If I don’t have a map prepared for a location that might host combat, I feel reluctant to run it (though I do have a stock of generic caverns to run those if they occur). The amount of time it takes to make a pretty map also means that more complex dungeons take that much more time to think of and then make. I find that the tactical depth a grid map adds to combat, combined with the automated rolling and damage calculations of VTTs is a really huge asset. Though it does make my players more prone to combat if they see me pull up a map (in their defense, they recently peacefully negotiated with driders even though I had their entire camp mapped and stat blocks prepared). I have, however, run many chase sequences in theater-of-mind, and other encounter types that really traverse a long distance and wouldn’t fit on a single map.

I’m about to have my party raid a mind flayer lair to steal some elder brain juice for a ritual. Mind-flayers have very “vertical” dungeons because they can levitate at will, so it’s definitely an opportunity for some [xandering] with multiple levels and three-dimensional loops. I’m not sure how they’ll survive if they actually alert the mind flayers though… those narrow hallways are really going to bunch them up for the brain-fry rays.

[…] straight to Area 14 and entered Fairyland. As much as I love nonlinearity and extol the virtues of [Xandering] the Dungeon I do feel that constructing the dungeon such that the party can waltz right into what feels like […]

The link at the bottom “Go to Part 2” is now broken. It has the new page name only, without the full alexandrian.net path, so clicking it goes to “http://xandering-the-dungeon-part-2-xandering-techniques/”

[…] a bit of it when people are really into it. They will talk about Gygaxian naturalism, or Jaquaysing Xandering dungeons [note check this Alexandrian post regarding the name change]. If it’s a Hickman […]

Lame that you changed this to Xandering.

Trying to scrub “jaquaysing” from the culture and replace it with “xandering” is quite draconian, perhaps even orwellian.

Jaquays didn’t create the method of having non linear dungeons.

The very first dungeon ever created, Blackmoor, was a mess of meandering hallways and up and down access points.

Jaquays created brilliant modules, with Enchanted Wood being my favorite of all. Yet, the method really was created by Dave Arneson.

[…] nigh-on essential in a good dungeon crawl is having multiple paths to explore. (I recommend reading The Alexandrian’s article on this technique.) I don’t really think you can meaningfully have a dungeon of multiple paths without some sort of […]

“Trying to scrub “jaquaysing” from the culture and replace it with “xandering” is quite draconian, perhaps even orwellian.”

It’s not draconian or orwellian at all. You don’t seem to understand either of those words.

You also don’t seem to even understand that the original term was Jaquaying, which isn’t even Jennell Jaquays’ name, and was a term she WANTED changed. So here you are Joey, trying to rewrite history, because you’re a viciously ignorant troll (even if that’s not your intent, you are absolutely trolling hard here, and getting tons wrong).

And since you’re too illiterate to read the comments before making your own, I will just add on to what is already repeated at your deaf ears: Jaquays didn’t invent this method. Justin Alexander was the one who created the work of “Jaquaying” the dungeon, and it’s actually not only more ethical to rename it Xandering, but more Just and accurate to the facts.

So here we have it, just the facts:

Fact 1.) Jennell didn’t like the term “Jaquaying” and wanted it changed.

Fact 2.) Justin Alexander invented the term “Jaquaying the dungeon” and is the original author of it.

Fact 3.) Justin Alexander went out of his way, IMO way too much, to appease Jennell and his critics, in changing the name.

Fact 4.) Justin Alexander is extremely pro-trans, and the people who criticize him like he’s some villain are always, like you, viciously ignorant trolls. That’s a matter of fact, as you can’t even get the names right.

You’re not alone here though Joey. Other trolls also have this problem – they also are so illiterate that their reading comprehension is horrible, they remain willfully ignorant of the facts, and, like you Joey, they can’t even spell the terms or names correctly because they don’t actually care about Jennell or her legacy – it’s all just emptyheaded virtue signaling for you. Perhaps you should seek counseling if all you desire on the internet is necrophilia – the mentally ill desire for death and destruction of everything around you. Joey the Troll.

Would it be possible to add another note, at the top of this article, with a link to your “A Second Historical Note on Xandering the Dungeon” blog post from January 2024? I’m not seeing any links to that post on this page, but I might not be looking in the right spot…

I only came across this article pretty much blindly, and was confused on the specifics of the discussion around the use of the terms “Xandering” and “Jaquaysing.” The “Second Note” article was very enlightening and answered most of the questions I had regarding the usage of the terms. I can understand the difficulty of changing the use of the term “Xandering” and of the historical value of keeping this article mostly the same, so that people have a clearer picture of why terms were used when they were, but a simple additional note should help clear up some confusion among the broader TTRPG community, and may help bridge some divides between folks.

I did want to thank you for previously taking the time to change all references to Jennell Jaquays’ deadname and old pronouns into her new name and pronouns, even if it did lead to some inadvertent harm after the fact. They were, at the very least, good intentions and seemed to come from a place of intended respect.